One day at Zoopla, it hit us: we were moving slowly, people were leaving, and we couldn’t clearly connect our work to the company’s goals—let alone revenue. We didn’t even know where to begin improving. It was draining.

We couldn’t keep that for too long. So, we started where we thought it mattered most: with culture. With people. With alignment. Leadership became about building thrust, clarity, and a motivated drive. We rallied. And in time, the business gave us another chance.

But as momentum grew, a bigger question emerged: how would we know if we were truly improving? We had DORA metrics. We had Peakon. We had a dozen data points—but none of them told the whole story. Or were terribly misleading. Like our metric, that our change lead time was within one day, but reality was we were taking months to deliver work.

How did this first stage unravel? The first steps, preceding the metrics?

Before you can measure what matters, you have to build what matters. Metrics alone weren’t going to fix what we were feeling: a growing disconnect, a loss of clarity, a culture misaligned with the pressure of constant delivery. We knew that chasing numbers without shared purpose would only deepen the problem. So we took a different path—one rooted in transformational leadership ((Bass & Riggio, Transformational Leadership, 2006). We focused on inspiration before instrumentation, setting a clear engineering vision and uniting people around common values, not just quarterly targets. Also explaining what value and performance means. Culture wasn’t an afterthought—it was our foundation.

We made bold choices. Technical debt wasn’t postponed—it became a strategic priority. Refactoring legacy systems, improving observability, modernizing our stack—these weren’t chores; they were acts of belief in a better future. Slowly, we made the business stop seeing this work as maintenance and made to start seeing it as momentum. And it gave us much pride.

We also reimagined how we brought people in. Hiring wasn’t a pipeline—it was a promise. We rebuilt our recruitment and onboarding to focus on alignment, not just aptitude: structured interviews, skills-based assessments, and a clear signal of who we were and what we stood for. Alongside this, we leaned into new tools—GitHub Copilot, other LLMs—not out of hype, but as an investment. We believed technology could support creativity, not replace it.

And perhaps most importantly, we wrestled with the question: what does good performance really look like? Not heroism. Not pat-on-the-back for each pixel. Not awesomeness and nice looks. Not hustle. But clarity. Sustainability. Growth. Value. Revenue. We helped our teams move away from vague praise and toward concrete understanding—what success meant, how it showed up, and how it grew with them. Research backs this up: clarity of expectations is one of the strongest predictors of performance and satisfaction (Gallup, State of the American Workplace, 2017).

This work wasn’t glamorous. But it was vital.

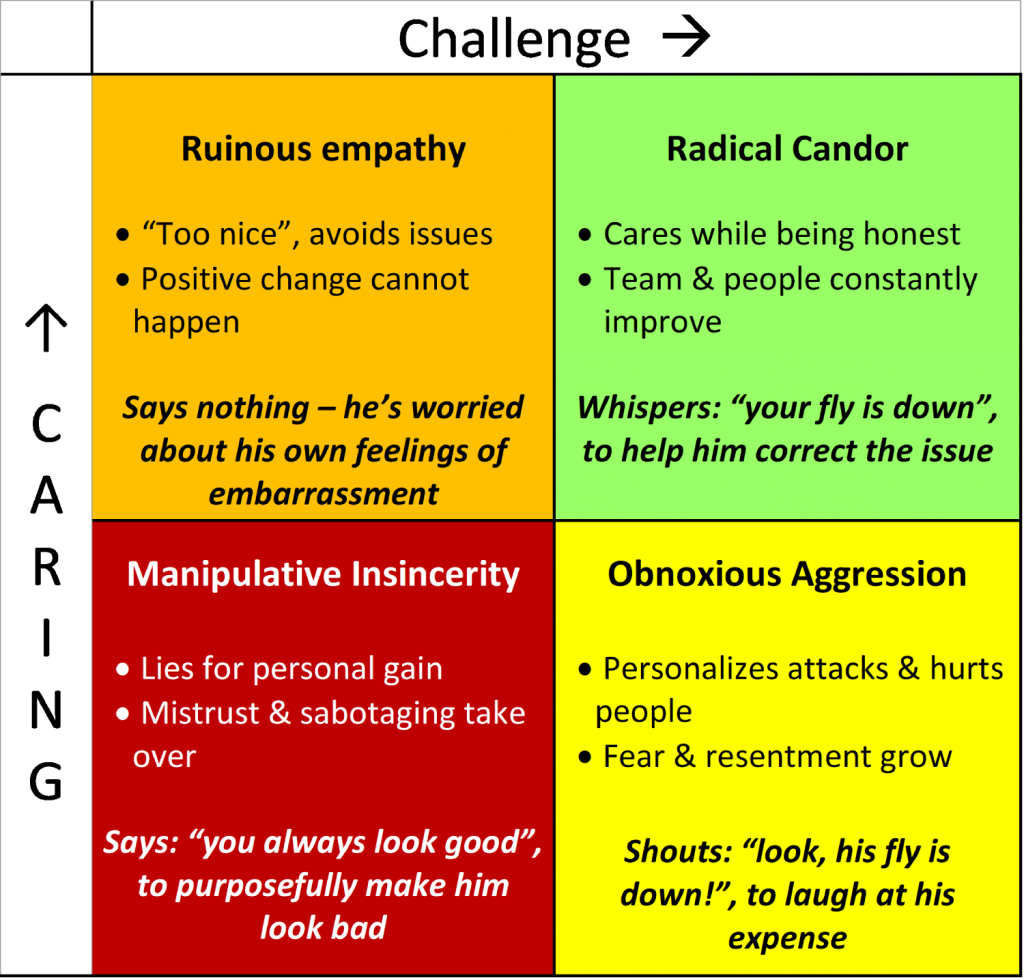

Equally important—maybe even more so—was the culture we built around feedback. Not the kind that hides behind anonymous forms or quarterly reviews, or just positive reinforcement, but real, human feedback: honest, direct, and rooted in care. We trained our leaders and teams in Radical Candor (Scott, Radical Candor, 2017)—the belief that the most meaningful growth happens when you care personally and challenge directly. It wasn’t about increasing the volume of feedback. It was about deepening its value.

Regular, respectful, and purpose-driven performance conversations became the heartbeat of our teams. Research shows this kind of feedback culture is a powerful driver of engagement, learning, and performance (London, The Power of Feedback, 2003).

So we didn’t leave it to chance—we designed it. Structured feedback patterns. Coaching rhythms. Peer recognition and adjustment loops. We worked to create a space where feedback wasn’t feared—it was expected, welcomed, and seen as an act of respect. And in doing so, we redefined performance conversations—not as judgment, but as shared commitment to growth.

All of this reflected a truth we held closely: transformation must come before measurement. If the cultural foundation is shaky, metrics become misleading signals.

And now we became ready to introduce metrics.

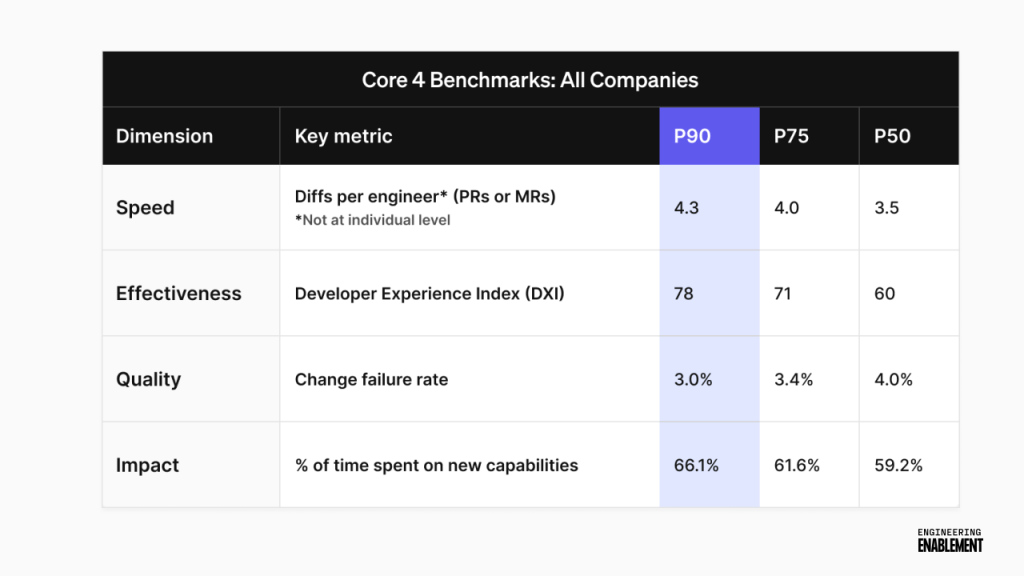

Eventually, we discovered DX Core 4.

The DX Core 4 framework—developed by DX in 2023—offered us a modern compass. Not to track velocity for its own sake, but to orient around four essential dimensions: Speed, Quality, Satisfaction, and Impact. These are not just metrics; they are pillars. Together, they form a shared language between engineering and business, one that transcends the misleading metrics of the past—lines of code, ticket velocity, or deploy frequency. (DX, Measuring Developer Productivity with the DX Core 4, 2023).

This framework draws from predecessors like DORA and SPACE. But where DORA emphasized throughput and SPACE valued wellbeing, DX Core 4 seeks synthesis. It invites nuance. Speed, here, is not haste but flow—how quickly value reaches users. Impact is not busyness but resonance—how deeply work aligns with business purpose.

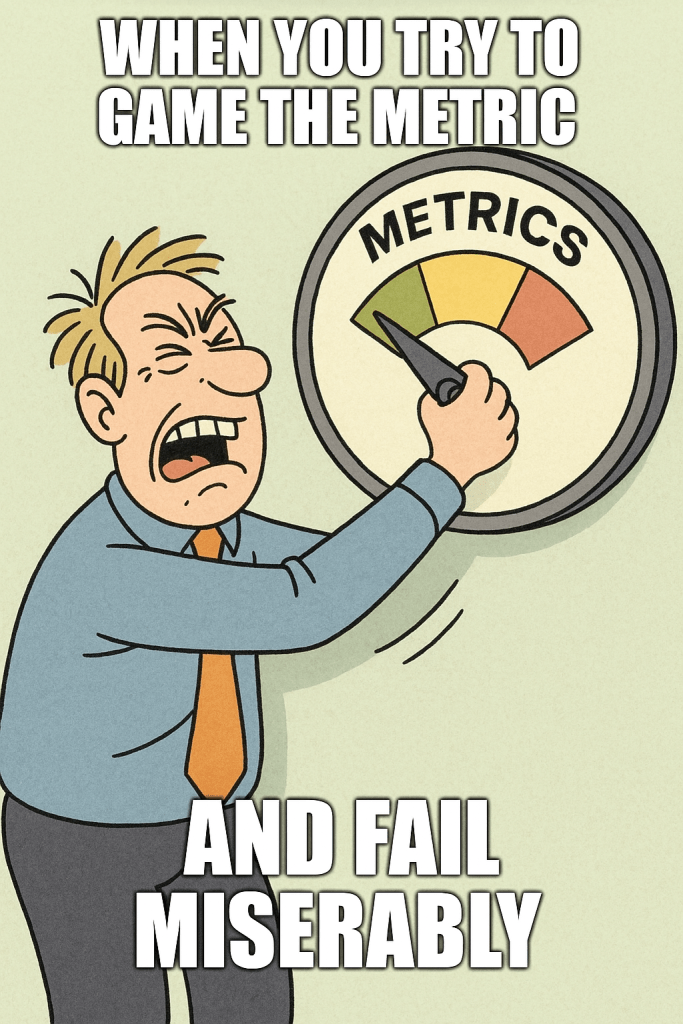

Yet the act of measuring people’s work is never neutral. History offers vivid warnings. The lesson is eternal: what gets measured gets managed—but not always for the better. Metrics don’t just reflect behavior. They sculpt it. If misapplied, even well-meaning frameworks sow dysfunction.

In modern contexts, the Wells Fargo scandal is a good cautionary tale. The bank set aggressive sales quotas for employees, leading thousands to open fake accounts to hit targets and avoid penalties. The result was a massive ethical breach, regulatory fines, and reputational damage. As the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau stated in its 2016 findings, “the bank’s incentive compensation program created a pressure-cooker sales environment that made it possible—and profitable—for employees to break the law” (CFPB, Enforcement Action against Wells Fargo, 2016).

We were well aware of the risks—after all, we’re experienced managers who’ve seen how metrics can distort behavior when misused. We understood that tracking the wrong things, or using data without context, often leads to unintended consequences. We also understood the risks of no measurement.

And we thought – how does DX Core 4 respond to that?

DX told us, Core 4 isn’t about tracking productivity for its own sake—it’s about reducing the risk of bad metrics driving bad behavior. Unlike older models focused on lines of code or ticket counts, it offers a balanced view across four pillars: Speed, Quality, Satisfaction, and Impact. This prevents over-optimizing one area at the cost of another.

Core 4 doesn’t turn data into performance targets. It surfaces trade-offs, invites context, and treats metrics as starting points for dialogue—not judgment. Like a dashboard in a complex system, it helps teams ask the right questions. Productivity becomes a shared responsibility, and data becomes a tool for improvement, not control.

Through our own research, we identified important limitations within the DX Core 4 framework, despite its promise as a multi-dimensional model for evaluating developer productivity across Speed, Quality, Satisfaction, and Impact. One key risk is metric distortion—where well-intended indicators are misused or gamed. For instance, a metric like “diffs per engineer,” aimed at tracking throughput, can incentivize superficial, frequent changes rather than meaningful contributions. This reflects a broader issue seen across domains: when outputs become targets, behavior shifts to meet the metric rather than the goal, as captured by Goodhart’s Law. (Goodhart’s Law; Strathern, 1997).

Moreover, DX Core 4 lacks a built-in theory of improvement, as noted by engineering leader Will Larson (Larson, Measuring Developer Experience Benchmarks & the Theory of Improvement, 2023). While it can diagnose symptoms—like low satisfaction or inconsistent delivery—it often fails to prescribe actionable remedies. The framework leans heavily on outcome metrics without offering guidance on the processes that drive change. As a result, teams may become data-rich but insight-poor, investing in measurement without clear direction for improvement. For DX Core 4 to be truly effective, it must be paired with qualitative insight, leadership intent, and a deliberate strategy for change.

Armed with understanding of the framework limitation, we deployed it.

Like the classic Hero’s Journey described by Stephen Gilligan and Robert Dilts, we experienced early enthusiasm, followed by deep challenges and moments of doubt. There were times when our performance metrics slumped and our confidence wavered—but through reflection, perseverance, and intentional leadership, we emerged stronger. And continue to be stronger and stronger.

What we see now, on the chart attached below is what we achieved. And now we use it to drive and measure our culture and progress towards value. The most recent signs of stability and improvement aren’t just numbers on a dashboard; they are the result of deep work, cultural renewal, and relentless commitment to doing things right.

While we originally set out to apply frameworks like DX Core 4 in full, the reality is more nuanced. At this stage, we’re still using tools like Peakon to track indicators of team efficiency and engagement. And we have some other indicators that we use instead of the original metrics. These serve as proxies for deeper performance understanding while we continue building out our measurement capabilities. Core 4 remains a destination, not a checkbox. The work continues, and we’re learning fast—what matters, what motivates, and what truly reflects impact. It’s a humbling and energizing process.

Of course, not all of this work is visible. We also have a much deeper set of metrics. Behind every emerging signal of progress is a day-to-day discipline of engineering rigor, feedback culture, leadership intent, and a great deal of unseen coordination. We’ve faced challenges around defining metrics, aligning stakeholders, and ensuring measurement supports—not hinders—our people. But we also recognize that the hardest parts are often the most valuable: in the messiness, we’ve found meaning.

And now? We’re past the blood, sweat, and tears. We’re no longer just reacting—we’re executing offensively, with purpose and pride. And can reasonably track that.

We didn’t just survive the journey—we integrated our learnings, we came out much stronger and we earned our right to lead!

Leave a comment