In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the human body is seen as an integrated whole where every organ, tissue, and even tooth is connected through an intricate system of energy pathways called meridians. This holistic approach views health not simply as the absence of disease, but as a harmonious balance of energies within the body. One fascinating and lesser-known concept in TCM is the relationship between teeth and the meridian system, and how dental health can reflect and affect the health of the entire body.

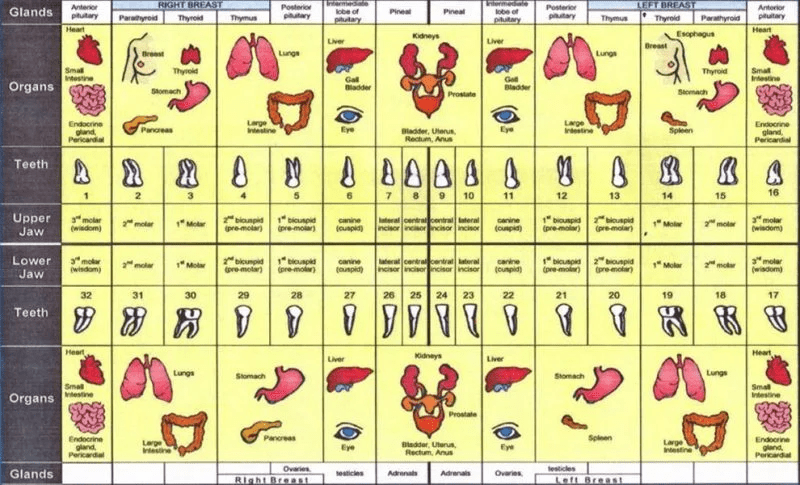

Each tooth, according to TCM, is energetically connected to different organs and systems through specific meridians. For instance, the upper and lower incisors are linked to the kidney and bladder meridians, the canines to the liver and gallbladder, and the molars to the stomach and spleen. This means that disturbances in the energy flow to or from an organ may show up as problems in the corresponding tooth, and vice versa.

This concept aligns with the TCM view that illness is not confined to one part of the body but is a sign of imbalance across the whole system. When a meridian becomes blocked or energy (Qi) becomes stagnant or deficient, it can manifest in a specific tooth as pain, sensitivity, or decay—even if conventional dental X-rays reveal no obvious pathology. Similarly, chronic dental issues might suggest underlying weaknesses or imbalances in associated organs.

The biological basis for this may not be as far-fetched as it sounds. Modern research has begun to explore the relationships between oral health and systemic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders. While these studies may not directly use the framework of meridians, they support the idea that the mouth is a gateway to overall health.

Studies that hint at this interconnectedness include:

- A review published in Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3590713/) explores the links between periodontal disease and systemic inflammation, supporting the TCM concept that tooth health reflects deeper systemic issues.

- Research in European Journal of Internal Medicine (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21111933/) discusses focal infection theory and the potential systemic effects of dental infections, resonating with TCM’s perspective of energetic and functional interconnectedness.

- A pilot study in The Journal of Pain (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31521794/) considers acupuncture meridians in dental pain relief and their neurological pathways, indicating that traditional concepts may have anatomical counterparts.

- And this (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11731113/) 2025 review highlights strong links between oral health and chronic diseases like diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular, and respiratory conditions. It explains that poor oral hygiene can worsen systemic inflammation and microbial imbalances, contributing to disease progression. For example, gum disease can impair blood sugar control in diabetics and may promote autoimmune responses in arthritis. The study underscores the importance of including dental care in chronic disease prevention and treatment strategies.

The concept of meridian-tooth connections invites a whole-body approach to both dental and systemic health. If an individual presents with recurring gum inflammation around the upper canines, a TCM practitioner may investigate liver health and emotional stress—since the liver meridian is closely tied to anger, hormonal balance, and the eyes. This cross-referencing allows practitioners to not only treat symptoms locally but also explore deeper root causes that may be affecting overall well-being.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), meridians are energetic pathways that link various parts of the body, including the teeth, to internal organs. For instance, the Kidney meridian is believed to connect with the lower central incisors (teeth 24 and 25) and plays a vital role in regulating the reproductive and urinary systems. Similarly, the Liver meridian passes through the canine teeth (teeth 6, 11, 22, and 27) and is closely associated with emotional balance, hormonal cycles, and vision. Disruptions in these meridians may manifest not only as dental discomfort but also as systemic issues such as mood swings, menstrual irregularities, or visual disturbances.

The Stomach meridian, which traverses both upper and lower molars, governs digestive function and the body’s overall energy levels. Dental problems in these teeth could indicate imbalances in the digestive tract, including poor nutrient absorption, fatigue, or gastrointestinal sensitivity. Meanwhile, the Heart meridian—which terminates at the tongue—also connects to the wisdom teeth. In TCM, this meridian governs not only cardiovascular function but also mental clarity and emotional wellbeing, making wisdom tooth pain or recurring inflammation a potential sign of deeper energetic disharmony.

Now this is an interesting thing and I am convinced there is something about general oral care and wider vitality. It begs a question – did we always needed a dentist?

Tooth decay, or dental caries, has not always been as prevalent as it is today. Anthropological studies reveal that early human populations, particularly hunter-gatherers, experienced low rates of dental caries. We generally link this to the diet. I have my doubts, as diet is usually the easiest thing to sell.

While it’s true that the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies introduced more fermentable carbs (which oral bacteria love), that alone doesn’t explain the sudden explosion of cavities in recent centuries. There are other key factors at play. For one, oral microbiomes have evolved alongside human behaviors. The diversity of microbes in ancient mouths was broader and likely more balanced. Modern lifestyles—antibiotics, mouthwashes, low microbial exposure, processed diets—have narrowed that diversity, letting cavity-causing bacteria like Streptococcus mutans dominate. A study published in Nature Genetics traced the oral microbiome in historical populations and found a major shift during the Industrial Revolution, coinciding with refined sugar consumption and reduced microbial variety (Adler et al., 2013).

Then there’s jaw development and breathing—areas rarely talked about but hugely relevant. Weston Price’s research in the early 20th century (though controversial) observed that people on traditional diets had broader jaws, straighter teeth, and less decay.

While diet is a significant factor in dental health, it’s not the sole contributor to the prevalence of tooth decay. Urban living introduces various elements that can impact oral health. For instance, studies have shown that adults residing in urban areas are more likely to have had a dental visit in the past 12 months compared to those in rural areas. Urban environments also expose individuals to higher levels of various pollutants, which has been linked to various health issues, including potential impacts on oral health.

Additionally, the modern urban lifestyle often involves increased stress levels, irregular eating habits, and higher consumption of processed foods, all of which can contribute to dental problems. Moreover, the proliferation of electronic devices in urban settings raises concerns about exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMFs). While some studies suggest that low-level EMFs can be used therapeutically in dental treatments, the long-term effects of chronic exposure to EMFs can’t be healthy (as mentioned in my article here: The Invisible Stress Around Us – A Personal Reflection on EMFs). Therefore, while diet remains a crucial factor, it’s essential to consider the broader urban lifestyle and environmental exposures when addressing dental health concerns.

I will take a very broad assumption here and say cavities, gum disease, and orthodontic issues were rare in ancient past. Teeth wore down naturally with age, but widespread decay, root canals, and fillings? These are largely modern phenomena.

The need for dentists exploded alongside modern urban lifestyles—processed diets, reduced chewing, altered oral microbiomes, environmental pollutants, chronic stress, mouth breathing, and perhaps even constant low-level exposure to artificial EMFs. These conditions didn’t exist for our ancestors. In contrast, traditional communities often maintained healthy teeth without toothbrushes, floss, or fluoride, simply because their environment, nutrition, and way of life supported natural oral resilience.

So yes, the evidence suggests that dentistry as we know it is a response to problems we created.

And both the Traditional Chinese Medicine and our modern medicine finds multiple links between oral health and general health.

All this points to a truth that is both sobering and empowering: modern dentistry is less a triumph over nature and more a necessary response to a lifestyle we’ve engineered—one that disrupts ancient biological rhythms, microbial ecosystems, and energetic flows alike. Traditional Chinese Medicine reminds us that the mouth is not an isolated compartment but a mirror of the body’s deeper currents. Whether we speak in the language of meridians or microbiomes, the message is clear—oral health is whole-body health. If we want to move beyond managing symptoms, we must begin to ask not just how to fix teeth, but why they break down in the first place. Maybe the best dentistry starts not in the clinic, but in how—and where—we live.

And as per usual I leave you with a thought – what if teeth are seen by our body as one of the less important parts and the decay is basically an attempt of the body to shift the illness away from something more important. Is then prioritising curing the teeth really healing, or our human-centric quick-fix, which pushes the illness deeper?

Leave a comment